It Carries Weight: Plus-Size Invisibility in Health and Fitness Advertising

- Jul 15, 2021

- 20 min read

Trigger Warnings:

Fat-shaming, mention of eating disorders and body dysmorphia, implied weight loss, ‘fat’ as a descriptive (for emphasis and rhetoric, not to fat-shame).

Content Warnings:

Implied dieting and diet culture.

Disclaimer

I want to make it clear that this isn’t about addressing ‘fat-shaming’ by ‘thin-shaming’ in return; it is not to degrade or belittle those that aren’t plus-size yet still struggle with body confidence, eating disorders, weight loss or weight gain. That is a separate topic that deserves its own time to explore with nuances and perspectives that I simply cannot provide. This piece will explore my opinions on plus-size visibility in health and fitness marketing; it is from the perspective of a plus-sized woman that has not experienced mentally harmful thoughts primarily centred around my weight, nor body dysmorphia. I don’t plan on writing an opinion on something I am not able to provide insight about. With that being said, I’m going to complain (again).

Fitting into the aesthetic

Have you ever applied to a retail job where you are required to wear their “high quality” clothes, but they don’t carry your size? During my ongoing hunt for employment, I applied for jobs at H&M even though I knew that even the simplest of items from the store, such as a vest top, would be a snugger fit than I would prefer ("Ribbed Vest Top - White - Ladies | H&M GB").

On the H&M section of Indeed, one person stated in a forum response that when it comes to H&M dress code, “H&M loves when you wear their clothes too because it represents the brand and I've gotten compliments from customers on my clothes and could tell them it's from the same store!” ("What's The Dress Code For Workers Like? | H&M | Indeed.com").

This forum response implies that even if you may not be penalised for not wearing clothes from the brand you work for, you benefit from illustrating the style and ‘wearability’ of their tops, jeans and shoes. But what if ‘wearability’ isn’t an option for you because sizes are too small? H&M’s vest tops go upwards to XL, which is technically a snug fit for me, but if I wanted to exhale or move, then I would be scuppered for choice on larger sizes. Not only that, but any body sizes that are above 2XL have no chance of finding a comfortable fit – so, if you are asked to be interviewed at a high-street retail store, you need to be sure that the store is literally the right fit for you. Why does job qualification and skill have to be compromised by a limited ‘work uniform’ size?

When I walked into an H&M store for the first time, I should have known that none of their items would fit me comfortably. But then again, I don’t think I have ever truly seen someone with my figure, width and shape in their window advertisements.

The first point of contact potential customers may have with retail stores are their window displays and any model photography. However, if plus-size bodies aren’t visible at all in product photos, then it's not feasible for big bodies to buy into the ‘desirable’ aesthetic that these brands want us to ‘achieve’ in the first place. If brands market to customers the idea that achieving a desired ‘goal’ has a recommended retail price, then they should be prepared to market to these target audiences properly. If any advertising or marketing campaign is targeting a specific audience to do something about the wellbeing of their body, then at least make the bodies you are targeting visible.

What’s my problem?

There is no question that body positivity or body neutrality is more commonly visible in advertising and marketing campaigns, such as SAVAGE X Fenty and the various body types that are hired to model the clothing (instagram.com/p/CPFXRq-rtSz/). My main frustration revolves around any product or service that aims to ‘solve the problem’ of obesity with health and fitness, or promotes weight loss...but chooses not to make ‘the problem’ actually visible. Why tell me to eat healthier supermarket food and lose weight when all the ‘thinny people’ pushing Sainsbury’s carts may not have ever been shamed into healthy eating to begin with?

So, what’s my problem? Well, many health and fitness advertising campaigns aim to communicate an ethos that may specifically target plus-size bodies to be proactive about their physical well being, but don’t actively invest in hiring plus-size bodies to model and partake in said ethos. I don’t just mean the one fat person in a group product photo or a specific post dedicated to showing off plus-size bodies, I mean fully integrating big bodies into brand modelling to signify that health and fitness is not exclusive to smaller body sizes.

I already have rock-bottom expectations because I’m not confident that my needs and wants are going to be solved, brands fueled by profit aren’t wish-granting lamp genies (although similarly dusty sometimes). However, I want to go into detail as to why health and fitness advertising are part of the problem they aim to ‘solve’ – such advertising can range from school meal campaigns to adult athleisure wear.

Biting Back

Ever since I taught my mum how to use Instagram, I have had the displeasure of her calling me regularly on the phone just to see her DM message. One of the things she has sent me was a video Jamie Oliver posted on his feed to support the @BiteBack2030 campaign with #BorisKeepYourPromise. I am biased towards celebrity chefs because their cooking shows were a staple of my upbringing; I even have a Gorden Ramsay Royal Doulton pasta dish that I may or may not had decided to claim four years ago when I was moving out of a shared house and it was left behind (no one will know...).

With that being said, Jamie’s video aimed to remind Prime Minister Boris Johnson “to keep his promise to protect their health and make sure that all young people have access to nutritious food, no matter where they live” (Oliver). This video consisted of portrait shots cutting from different school kids that have been affected by the pandemic and its lockdowns, acting as a collated message to Boris Johnson so he keeps his ‘promise’ to ensure young people have access to nutritional food (Oliver).

I understood the sentiment behind the campaign and also wanted healthy eating to be far more accessible for children, especially for those in low socio-economic households; however, I found one flaw with the video – and no, it wasn’t the young white boy saying he was deeply affected by the pandemic because he missed football. Where are the fat kids?

“It’s probably to show that the kids want to stay healthy,” my mum tries to reason. I reply, arguing that yes, the kids may want to maintain a ‘healthy’ weight. But for a public figure to emphasise how child obesity is a ‘problem’ to ‘solve’, and then refuse to make the ‘problem’ visible is short-sighted. Society has frequently criticised fat people for being fat and commented that they should stop being fat through means such as good health and fitness – so why put all this effort into making plus-sized bodies visible to criticism when they are invisible in advertising and campaigns that are dedicated to ‘good health’ in the first place? All this health and fitness rhetoric directed to plus-sized bodies as a target audience – and then not even representing that target market in the campaigns – seems counterproductive to me.

Jamie Oliver is known for using his access to television, book deals, and social media, to campaign for access to healthy meals in schools – to make sure that childhood obesity is halved by 2030 in the UK (Oliver). However, if Jamie Oliver cares so much about stopping child obesity, then for me it would be logical to illustrate how the pandemic made it less accessible for families with plus-sized kids to start or maintain healthy meal plans. This short-sightedness isn’t just from one video Mr. Oliver posted on this Instagram, it is also visible how invisible fat bodies are in the “Bite Back 2030” Instagram account.

An example of this ongoing invisibility was a photo posted by “Bite Back 2030” that addressed how the British Government voted against an amendment to put their food standards into law and how the campaign for universally healthier eating standards is ongoing. Once again, I have no particular issue with this photo highlighting a diverse community of people that want Britain’s health standards to improve without putting a dent in shopping budgets, especially with how much the pandemic has significantly affected individual and family incomes.

This photo aims to communicate that young people are also demanding change from the government, because youth is a powerful force for change when taken seriously. However, the absence of faces with double chins and bodies that are visibly bigger accompanied by the slogan #SaveOurStandards leaves a stale aftertaste when viewed through a plus-size lens. Arguably, the invisibility of fat bodies implicitly signifies that the ‘standard’ “Bite Back 2030” wants to ‘save’ is exclusively thinner – that the standard is thinner. Although this may not be intentional, the idea that big bodies aren’t present in the ‘standard’ highlights the greater discourse about fat people being visibly critiqued for their fatness. Arguably, this perpetuates the idea that fat people do not take healthy eating as seriously as thinner people.

Why would we take good health seriously? We’re fat. Why would we express autonomy to improve ourselves on our own terms, despite the continual shame we may experience? We’re fat. We’re fat therefore we are not a concern to campaigns that want to label our fatness as a societal issue. With this whole example trying to illustrate the importance of youth and their wellbeing, what does it say to plus-size youth when their wellbeing isn’t part of the picture?

How can a plus-size kid even think about healthy eating without the connotations of ‘fat = bad’ and ‘losing weight means social acceptance’, if public figures like Jamie Oliver don’t amplify the voices of plus-sized kids the same way he specifically chose to amplify non-plus-sized voices? He wants obese kids to not be obese, so where are the fatter body types when these campaigns are most likely designed to ‘solve’ fatness?

Discourse about representing body diversity in various media continues like ageing cheese – the longer it exists, the stronger it will be. It is important to keep this topic going to recognise that plus-size bodies aren’t one type of shape, width proportion, height, or ability. However, I want to continue addressing (ranting) about the decisions most western media decides to make about health and fitness advertising, in which target fat people are visibly shamed into idolising athleticism, but make accessible solutions and invisible for campaigns such as athleisure wear.

‘Plus-size’ in retail athleisure

It is possible for brands and retailers to carry plus-size options, but what becomes limiting for those that want to wear athleisure is how accessible and visible these options are. JD Sports, a UK sports fashion retailer, exemplifies these limitations.

Although JD Sports does provide a ‘plus-size’ category for online shopping, it is only an option to click under the ‘womens’ category** ("Plus Size"). There are two issues with this. The first is the implication that either ‘menswear’ does not need a plus-size category, or that ‘womenswear’ requires a plus-size category to signify that plus-sizing is exclusively marketed as a ‘womens’ concern; let’s not forget how clothes have no inherent gender but are gendered to reinforce insecurity-driven status quos, ones that sustain patriarchal systems and marginalised the LGBTQIA+ community. The second issue is that the idea of a ‘plus-size’ category in the first place suggests that JD Sports acknowledges the need for clothes that fit larger body sizes, but separate it from smaller sizes to implicitly segregate plus-size bodies as ‘other’ in retail shopping.

The decision to have a ‘plus-size’ category for online shopping is pointless if JD Sports does not take the initiative to actively advertise that their shopping experience is not exclusive to visibly fit-looking and ‘thinny’ people. Why bother having such a category if you don’t plan on making the option visible in product photos?

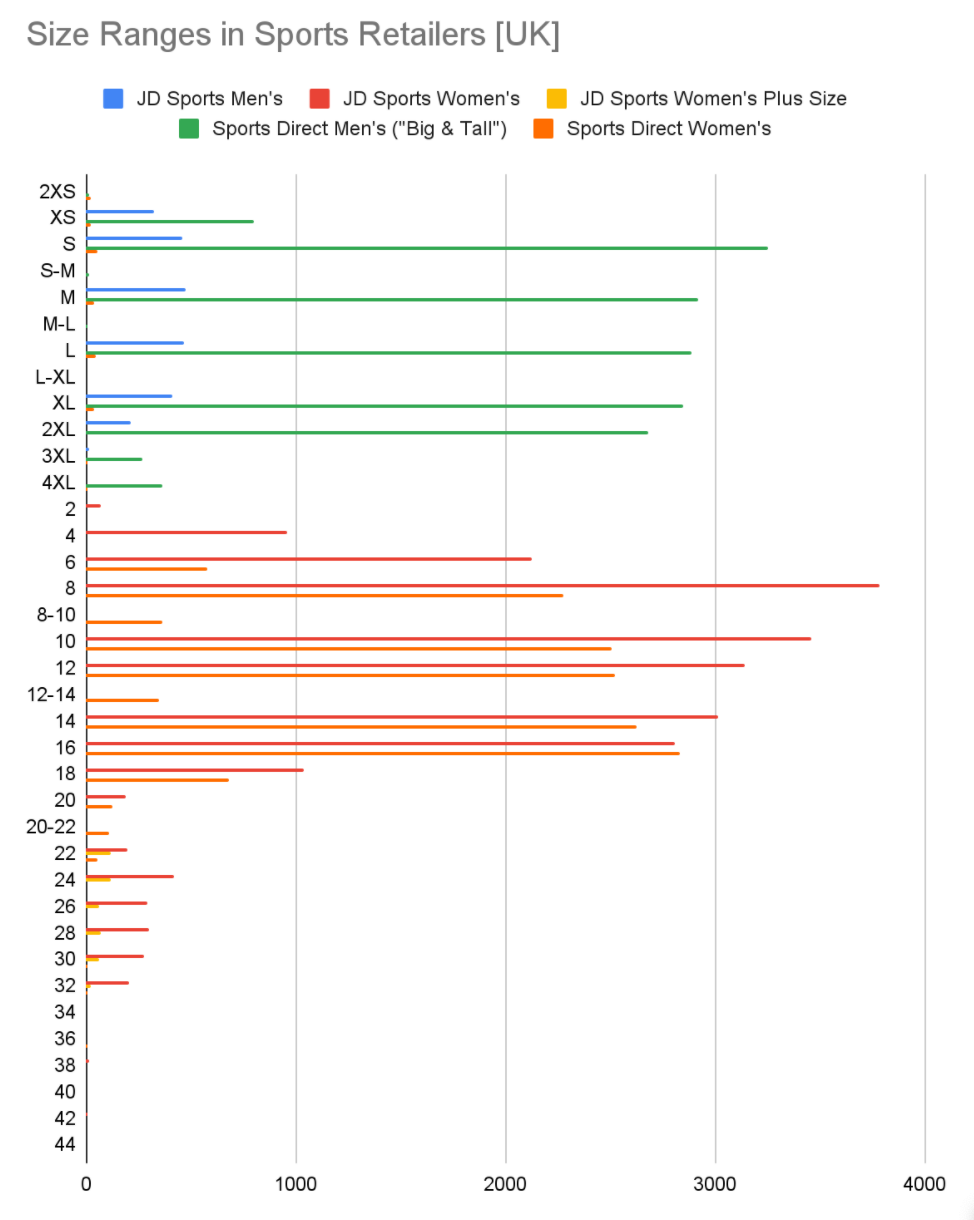

Even though a ‘plus-size’ category is a back-handed step towards body inclusivity, the amount of specific sizes highlights the fact that a ‘plus-size’ category does not inherently solve the fact that the brands a retailer stocks can carry a limited variety of sizes. These are three charts with data I extrapolated from the ‘Men’s Clothing’, ‘Women’s Clothing’ and ‘Women’s Clothing Plus Size’ pages:

Based on the data extracted from two of the major sports retailers in the UK, this further illustrates that potentially possibly perhaps maybe brands and retailers supply largely to a specific ‘mid-range’, meanwhile plus-sizes dwindle the higher the waistline. The fact that there can be a a huge jump from 1042 items for those size 18 to a measly 192 for size 20 in comparison under ‘JD Sports Women’s’ exemplifies how a ‘plus-size’ category in athleisure shopping is as performative as golfers shuffling their feet for alignment – a way to show off but easy for viewers to miss. Good luck to anyone a size 44, there is one item for you in Sports Direct online; a “KJUS Brissago Jacket” that was £209.99 (holy mother of crabcakes) but now to £65.00 (better, but not £2.90 better). I don’t know what’s more astonishing, how ridiculously inconsistent size ranges are for plus-size bodies to select for fitness, or how much that KJUS jacket was…("KJUS | Brissago Jacket Ladies | Full Zip Fleece Tops | Sportsdirect.Com").

In terms of performative visibility, the social media marketing for fitness brands is also a culprit. When you scroll through brands such as Nike, Adidas, Sports Direct or JD Sports and their Instagram accounts, the limited visibility of plus-size clothing and big bodies wearing athletic clothing is the equivalent of finding my mum at a golf course – she was present once on the rare occasion but she was not expected to be actively present regularly.

With brands that signify a specific ethos about athleticism and fitness, I can see how there is more investment to market celebrity status athleticism on social media to rile up motivation from target audiences. These images illustrate that ‘with enough willpower, drive and hard work, you too can be the best version of yourself just like these athletes with muscles that bulge out like broccoli stalks.’ This is evident with JD Sport’s centering their company values and branding around “the everyday athlete” ("JD Sports"). The ‘everyday athlete’ may signify that the retailer aims to supply resources for ‘everyday’ people that proactively involve themselves with fitness and athleticism on an ‘everyday’ basis to achieve extraordinary results – broccoli muscle and all.

With this in mind, wouldn’t the ‘everyday athlete’ also be applicable for plus-size bodies? It is a statistical fact that even if the commitment to New Year’s Resolutions depletes in February (Murphy), the top common resolutions revolve around losing weight, dieting or going to the gym (Ballard; Ibbeston). Although these resolutions are not size-exclusive, they are often associated with plus-size bodies or general weight gain prior to New Year’s Day (even if you’re like me and think goal setting is for any day because January 1st places a lot of unnecessary pressure with expectation to fail).

Therefore, it would make logical sense that for any time of the year, fat bodies have the autonomy to be proactive about physical wellbeing. Multiple retailers and companies have profited from insecurity-driven resolutions to boost sales on weight loss resources, so wouldn’t it be a nice change to see New Year’s advertising with plus-size models that express body autonomy to do whatever is best for their individual wellbeing? Not to shame fat bodies into dieting. Not to shame fat bodies that ‘fail’ their resolutions. But to just acknowledge that there are options and any option is valid for any size. If you want to improve your wellbeing and exercise like an ‘everyday athlete’, then there are brands that can cater to your size to assist the journey at your own pace...Idealistic, isn’t it?

Fat people can be ‘everyday athletes’ too but for JD Sports, they only care about highlighting ‘everyday athletes’ with broccoli muscle on social media – because I guess a fat person aiming to be a less-fat person doesn’t maximise ‘double-tap’ potential. This does not help with the fact that these social media accounts utilise body envy to market their brand and company values, but don’t actively solve the problem of body envy for plus-size bodies in a way that makes us feel seen rather than exposed.

Let's say you were told to ride a bike, but all the bikes available to you had no wheels – and no one sees why a bike with no wheels is counter-intuitive. Let's say your goal is to hit a hole-in-one, but you have no golf ball or putter – you are immediately set at a disadvantage. Fat bodies being told to go to the gym, with no clothes available for fat bodies to wear at the gym, is counter-intuitive and immediately sets a disadvantage.

If people set expectations on plus-size bodies to invest in their health and fitness, we should set expectations on health and fitness campaigns to invest in plus-size bodies too.

“Promoting an unhealthy lifestyle”

Social media, and media in general, has continued to police the way big bodies are perceived as an ‘unhealthy standard’; an example of this would be when Facebook had to apologise for banning a photo of Tess Holiday (a plus-sized model) because according to its ‘health and fitness’ advertising policy, her body size promoted something that was a violation of their guidelines (Levin). Facebook's initial defense, which they later retracted with an apology, stated that “Ads may not depict a state of health or body weight as being perfect or extremely undesirable”, and “Ads like these are not allowed since they make viewers feel bad about themselves. Instead, we recommend using an image of a relevant activity, such as running or riding a bike” (Levin).

Yikes.

The mental gymnastics someone would have to go through to bend to a platform’s guidelines, to imply that body insecurity triggered by a photo of a plus-size body can be solved with bikes. An interesting take about policing big bodies – not a good one – but I guess I’ve yet to solve fat shaming with bike helmets and bells so I won’t knock it (accept I will because Facebook’s defense was yikes).

This one ‘incident’ has contributed to a greater discussion about how people often project this notion that plus-sized bodies inherently promote ‘an unhealthy lifestyle’ that isn’t suitable for representation in health and fitness campaigns. But surely, that’s counter-productive.

“We don’t want to encourage obesity”; okay, but I haven’t seen glamour shots of flabby bingo wings glistening in the sun during a Sunday Funday run. Do glamour shots of fat people partaking in healthy physical activities encourage an unhealthy lifestyle? Do glamour shots of a fat person running in sleek jogging bottoms, that glide any static friction from chub rub, encourage an unhealthy lifestyle? Do glamour shots of someone with wide feet putting on their favourite pair of tennis shoes that fit them encourage an unhealthy lifestyle? Do glamour shots of someone with a protruding double chin enjoying grilled halloumi encourage an unhealthy lifestyle? For goodness' sake, do glamour shots of a plus-size person playing golf encourage an unhealthy life too?

What health concerns are there for a sports and fitness company to think a big person can’t swing a high performance supersonic ultimate XXX multispeed titanium wedge? I’m sure there are more than a few high earning or retired people that enjoy playing on the green and have polos larger than Callaway umbrellas.

I grew up going to golf clubs for fun (we all have a dark past) and if you are in any way familiar with typical British pub menus, I can guarantee you that none of the blokes at these clubs quenched their appetite with a succulent meal of kombucha and pomegranate couscous. If I remember correctly, beer and battered sausage baguettes are not superfoods of the PGA tour. So, what’s the problem making fat people visible for any sports ad? Not glamorous enough to signify the lifestyle you want target audiences to spend money to achieve? Why are we missing out on health and fitness campaigns when these campaigns so desperately want us to ‘fit in’ the ethos of healthy living?

Why are plus-size bodies missing?

I don’t need to beat anyone’s head over the established fact that societies of any kind have some level of ‘beauty standard’, something that categories people in ‘accepted’ and ‘not accepted’ according to an arbitrary set of characteristics that change throughout history and culture. Based on the idea of a beauty standard, industries have historically relied on socially accepted visuals to attract viewers with ‘eye candy’ to reinforce this standard as the superior image that you can only attain and maintain if you have the genetics, resources, or money. Especially the money.

This means that plus-sized bodies with knobbly wobbly bits have been consistently categorised as ‘not accepted’ according to whatever beauty standard has been established for that decade. Since western society did not associate ‘fat’ in proximity to ‘pretty’, this implied that big bodies were not desirable enough to sell products to a customer – whether it be thigh-hugging jeans or even a potato slicer!

In my opinion, another facet to the invisibility of plus-sized bodies in advertising is to target this demographic with the beauty standard, to target fat people with what they should aspire to look like. Robin Givhan and Hannah Reyes Morales argue that “[…] on a powerfully emotional level, being perceived as attractive means being welcomed into the cultural conversation. You are part of the audience for advertising and marketing. You are desired. You are seen and accepted. When questions arise about someone’s looks, that’s just another way of asking: How acceptable is she? How relevant is she? Does she matter?” (GIVHAN and REYES MORALES).

Givhan and Morales’s final three questions exemplify why I believe plus-size bodies have been so invisible in advertising for so long. It’s not just about this arbitrary beauty standard, it’s about whether or not society believed that plus-size bodies ‘mattered’ in the public? Do they matter enough to be seen? For a long time and to this day, western societies want fat bodies to do something about their fatness, but only as long as fat bodies aren’t seen during the progress of the changes that societies wants us to make; “I don’t like how you look so I won’t look at you until you are different”. But this can’t possibly be logical if you are a health and fitness brand. You simply can’t expect fat bodies to go away until ‘the problem’ is solved when YOU display yourself as the problem-solver.

Why would plus-size people aspire to a body type they already have if they can aspire to a thinner and ‘accepted’ body size? By marketing primarily with aspiration rather than representation, health and fitness advertising can reinforce a societal ‘problem’ without having to actually hire ‘the problem’ as faces of the campaign.

What do I want?

To summarise my thoughts, feelings and aggravations – health and fitness brands do very little to make the main target of being shamed into ‘healthy living’ feel welcomed in their advertising. Simply put, it is hypocrisy. It is not enough to present expectations and promote a lifestyle or aesthetic as an ‘aspiration’ if the options for big bodies to access a lifestyle to ‘aspire to’ is invisible on public advertising.

Whether it be high street retail dress codes, window shopping, online shopping, or politically charged campaigns, health and fitness brands need to swallow a bitter, low-calorie pill that their marketing does very little to actually serve a demographic that may need it the most. Visibility has value; it carries weight.

When fat people are shamed for being fat;

When fat people are considered a threat to long-term wellbeing;

When fat people only have to exist for public criticism about an ‘unhealthy lifestyle’;

When fat people are told to do something about their weight to ‘better themselves;

When fat people are told ‘go to the gym’;

When New Year’s resolutions place an unnecessary expectation to change fatness into ‘fatless’;

When brands have made it their mission to market a solution to a problem exacerbated to fat people;

When brands say ‘we can provide everyone options to improve themselves, but it’s not fit for everyone’;

What are fat people expected to do?

How do health and fitness campaigns expect us to run a relay race without giving us the baton? We are set up to expect failure. We are set up to give up. We are set up to continue being the ‘others’ of a ‘healthy’ society. We are continuing to see a decline in the popularity of dieting culture in public discourse, but plus-size bodies continue to be visible to criticism and invisible to opportunity.

This isn’t simply about me ‘seeing myself’ in advertising, and it is more than just wanting body inclusivity for diversity. I want brands and campaigns that champion better health and fitness to acknowledge that they are part of the problem. If I am expected to see more McDonald’s chains than accessible gym wear that caters beyond my size – that is a problem.

I want any fitness campaign to really think about this question: who are you fit for?

Fat people get chewed up by the public expectation, but we bite back.

- Hannah G

An opinion piece about the hypocrisy of brands advertising health and fitness towards plus-size bodies, yet have exclusively ‘healthy’ looking body sizes hired to model these campaigns.

**In terms of the ‘womenswear’ and ‘menswear’ labels, I personally believe that clothes are genderless; such categorisations can reinforce gender stereotypes and do not support gender non-conforming. 'Womenswear' and 'menswear' have been written as such in this piece for consistency when referring to retail labelling, but does not reflect my support to dismantle binary gender labelling in the clothes industry and athleisure.

Writer's Sources:

"Big And Tall: Plus Size Clothing For Men And Women | Sports Direct." Sportsdirect.com. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Biteback2030." Instagram.com. N.p., 2021. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Body Image Survey Results - Women And Equalities - House Of Commons." Publications.parliament.uk. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Callawaygolf." Instagram.com. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Chinese Clothing Size Charts - UK Size Charts - Jade Bagua Ltd." Jadebagua.com. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Engage, Empower & Support. 🏌️♀️⛳️ Join Us As We Celebrate Girls And Women Playing Golf And Learning Skills That Will Last A Lifetime. #Womensgolfday 2W." Instagram.com. N.p., 2021. Web. 18 June 2021.

"JD Sports." Facebook. Web. 25 June 2021.

"Jdsports." Instagram.com. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Just A Bit Of Friday Fun! 😂 You've Seen The Meme Women Laughing Alone With Salad But Have You Seen Men Laughing Alone With Fruit Salad? 🥗 Clearly, Salads Are Just Hilarious Food To Eat And If You Eat Them It Will Give You This Much Joy! 🤣." Instagram.com. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

"KJUS | Brissago Jacket Ladies | Full Zip Fleece Tops | Sportsdirect.Com." Sportsdirect.com. Web. 25 June 2021.

"Men's Latest Clothing." JD Sports. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Nike." Web. 18 June 2021.

"Nikesportswear." Web. 18 June 2021.

"Plus Size." JD Sports. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Ribbed Vest Top - White - Ladies | H&M GB." H&M. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Ribbed Vest Top - White - Ladies | H&M GB." H&M. Web. 18 June 2021.

"SAVAGE X FENTY | Lingerie By Rihanna UK." Savagex.co.uk. N.p., 2021. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Verified Snatchin' Trophies 🏆 We Just Snagged 3 #Webbyawards For The #SAVAGEXFENTYSHOW VOL 2. Check 'Em Out At The Link In Bio. Cc: @Amazonprimevideo & @Mojosupermarket." Instagram.com. N.p., 2021. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Verified The Honeybeez: Dream Crazier “Any Dream Is Possible. If You Just Want This Crazy Dream To Happen, You Just Have To Put The Work In." ⠀ You Know What Some People Consider A Crazy Dream? A Body Positive World. One That's Full Of Confidence. A World That’S Dripping In Self-Love. ⠀ But That’S The "Crazy” World That Montgomery’S Honeybeez Are Fighting For. #Justdoit." Instagram.com. N.p., 2019. Web. 18 June 2021.

"What's The Dress Code For Workers Like? | H&M | Indeed.Com." Indeed.com. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Womens Plus Size | Jackets, Dresses, Jeans, Underwear, Tees | Sports Direct." Sportsdirect.com. Web. 18 June 2021.

"Womens Plus Size | Jackets, Dresses, Jeans, Underwear, Tees | Sports Direct." Sportsdirect.com. Web. 25 June 2021.

"Yesterday Didn’T Go Our Way. The Government Voted Against An Amendment To Put Our Food Standards Into Law, So That Any Changes To Them Would Need A Vote. We’Re Disappointed, But We’Re So Grateful For The 46,000 Of You Who Emailed Your MP To #Saveourstandards. This Doesn’T End Here. We’Ll Be Working To Make Sure Child Health Has A Voice In Our Trade Deals. As Our Youth Board Member Rebecca Morgan Puts It “We Stand By The Call To Give ALL Young People The Opportunity To Be Healthy And Have Access To Good Quality Food And Standards No Matter Where They Live, A Call Which We Hope The Government Will Hear.”." Instagram.com. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

"“You Just Have To Take A Leap Of Faith. Be Who You Wanna Be, Wear What You Wanna Wear, And Go Big Or Go Home. Whatever You Do, You Just Have To Come Out There Stepping,” @Asuhoneybeez.." Instagram.com. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

Ashley, Beth. "What Happened To Plus-Size?." Vogue Business. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

Ballard, Jamie. "Exercising More And Saving Money Are The Most Popular 2020 New Year’S Resolutions | Yougov." Today.yougov.com. N.p., 2020. Web. 25 June 2021.

Blitzresults.com. Web. 18 June 2021.

Chun‐Yoon, Jongsuk, and Cynthia R. Jasper. "Garment‐Sizing Systems: An International Comparison." International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology 5.5 (1993): 28-37. Web. 18 June 2021.

DALL'ASEN, Nicola. "Where Are All The Fat People In Beauty?." Allure. N.p., 2021. Web. 18 June 2021.

Galassi, Madeline, and Beth Gillette. "We Ventured To Nike To Try On Their New Plus-Size Activewear—But This Happened Instead." The Everygirl. N.p., 2019. Web. 18 June 2021.

GIVHAN, Robin, and Hannah REYES MORALES. "The Idea Of Beauty Is Always Shifting. Today, It’S More Inclusive Than Ever.." National Geographic. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

Ibbetson, Connor. "How Many People Made New Years Resolutions For 2020? | Yougov." Yougov.co.uk. N.p., 2019. Web. 25 June 2021.

Levin, Sam. "Too Fat For Facebook: Photo Banned For Depicting Body In 'Undesirable Manner'." the Guardian. N.p., 2016. Web. 18 June 2021.

Marsia, Amanda. "How To Convert Asian Size To US/EU Size (Clothes/Shoe Size Chart)." Chinabrands.com. N.p., 2019. Web. 18 June 2021.

Martin, James. "How To Find Your Clothing Size In Europe." TripSavvy. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

Oliver, Jamie. "Jamie's Plan To Tackle Childhood Obesity | Features | Jamie Oliver." Jamie Oliver. N.p., 2018. Web. 18 June 2021.

Oliver, Jamie. "Tomorrow, The Government Sets Out Their Priorities For The Next Year To Build Back Better As A Nation. All Of The Young People At @Biteback2030 Are Calling On Boris Johnson To Keep His Promise To Protect Their Health And Make Sure That All Young People Have Access To Nutritious Food, No Matter Where They Live. I Need You To Stand Alongside Them. If You Do Just One Thing Today, Please Click The Link In My Bio To Sign The Letter And Add Your Voice. #Boriskeepyourpromise @10Downingstreet." Instagram. N.p., 2021. Web. 18 June 2021.

Roach, Andrew. "Convert Asian Sizes To US Sizes – Asian Size Conversion Chart." Oberlo.co.uk. N.p., 2020. Web. 18 June 2021.

Vagianos, Alanna. "What The ‘Ideal’ Woman’S Body Looks Like In 18 Countries." HuffPost UK. N.p., 2021. Web. 18 June 2021.

Editors: Bri. S, Lee. L, Lin. M.

Comments